California's Infamous Stage Robber

BLACK BART THE LEGEND BEGINS

Charles E. Boles

aka Charles E. Bolton

aka BLACK BART

A deep voice commanded: "Please throw down the box!" Bart then said, "If he dares shoot give him a solid volley, boys." Shine looked around and protruding from the boulders on the hillside were what appeared to be six rifles. Shine quickly reached beneath his seat and withdrew the Wells Fargo strongbox (a wooden box reinforced with iron bands and padlocked) containing $348, according to Wells Fargo, and tossed it and the mail sacks to the ground. Shine warned his passengers, eight women and children and two men2, to refrain from doing anything stupid. One of the women travellers threw out her purse in panic. Black Bart reportedly picked it up, bowed to the lady, and handed it back to her. "Madam, I do not wish your money," he said. "In that respect I honor only the good office of Wells Fargo."

With a sweep of his hand Bart motioned Shine on his way. As Shine drove away the driver took a quick glance back and saw the man attack the strong box with a hatchet. Shine drove off some distance and then stopped the stage. Shine's stage had barely gone up the hill when a second coach, driven by Donald McLean of Sonora, started up the hill and came upon the robber hacking away at the treasure box. McLean stopped the stage and Bart asked him to throw down the express box. McLean, with the double barreled shotgun pointed at him, said that he did not have an express box3. Believing the driver, Bart told him to drive on, unmolested. McLean caught up with Shine's stage at the top of the hill. The drivers and a couple of male passengers walked back down the road, saw a half dozen guns leveled at them from outlaws positioned behind boulders. They stood still and then realized the outlaws were not moving. It was sticks pointed at them from the boulders.

1 This is the only robbery that Bart carried more than just a shotgun.

After the robbery Bart stopped at a farm asking for directions and sold the Henry rifle to the farmers

wife for $10.00.

2 One of the two men on the stage was one of the owners, John Olive. The other passenger was a young miner.

When Bart stopped the stage the young miner went for his gun but John Olive grabbed his wrist and foced the

gun to the floor. He said to the young miner "Put that damned thing away, do you want to get us all killed."

3 There was sort of an unwritten rule between drivers and robbers that if the driver said there was no treasure

box on the stage the robber would not press the issue. However, if the robber found out later that the driver

had lied, the next time the robber causht up to the driver, he probably would shoot him.

The legend was born; Black Bart had committed his first robbery.

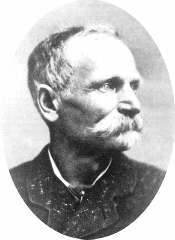

Charles E. Boles (aka Black Bart, aka Charles E. Bolton) lived in San Francisco.

He was a man well into his 50's, about five-foot eight inches tall, ramrod straight, with gray

hair and a moustache. A natty dresser, he favored diamonds and carried a short cane.

People seeing him walk down the street in 1870's San Francisco would

have thought him nothing more than a kindly, prosperous, old grandpa

out for a leisurely stroll. But, he was more than that, much, much more.

No one could have imagined that this man was really the famous, or

infamous, Black Bart the stage robber-poet of Northern California,

or P o 8, as he preferred to refer to himself.

He was a man who liked to live well and intended to do just that. He stayed in fine hotels,

ate in the best restaurants and wore the finest clothes. Now all he had to do was find a

way to earn a living to support his preferred lifestyle, and Charles E. Boles found a dandy.

Bart was not a rampant pillager of Wells Fargo. He only

robbed stages periodically, sometimes with as much as nine months

time between robberies. He later stated that he "took

only what was needed when it was needed." Most stagecoach

drivers were submissive to Bart, seldom defying him with a cross

word and obediently tossing down the strongbox when ordered to do

so. This was not so with hard case George W. Hackett who, on

July 13, 1882, was driving a Wells Fargo stage some nine miles

outside of Strawberry, California. Bart suddenly darted from a boulder

and stood in front of the stage, stopping it and leveling a

shotgun at Hackett. He politely said: "Please throw down

your strongbox." Hackett was not pleased to do so; he

reached for a rifle and fired a shot at the bandit. Bart dashed

into the woods and vanished, but he received a scalp wound that

would leave a permanent scar on the top right side of his forehead.

The lone bandit continued to stop Wells Fargo stages with

regularity, always along mountain roads where the driver was

compelled to slow down at dangerous curves. It was later

estimated that Bart robbed as much as $18,000 from Wells Fargo

stages over the course of his career, striking twenty-eight times.

He left no clues whatsoever, although he did leave a spare gun

after one robbery. He was always extremely courteous to

passengers, especially women travelers, refusing to take their

jewelry and cash. He made a favorable impression on

drivers and passengers alike as a courteous, gentlemanly robber

who apparently wanted to avoid a gunfight at all costs.

On July 30, 1878 while robbing the stage from La Porte to Oroville,

Black Bart added to his legend. Again a woman traveler attempted to get out of the

stage and give up her valuables to Bart. Black Bart stopped her and said: "No lady, don't

get out. I never bother the passengers. Keep calm. I'll be through here in a minute and on my

way." With that he took the express box containing $50 in gold and a silver

watch, the mail sacks and was on his way.

With his loot, Bart had invested in several small businesses which brought

him a modest income, but he could not resist the urge to go back

to robbing stages when money became short.

After so many successful robberies, the P o 8 thought his luck would

continue forever, but it was not to be. On November 3,1883, his luck ran out.

Why did Charles Boles decide to call himself Black Bart? Bart himself told Harry Morse and

Captain Stone why when they were going out to pick up the gold alamagam from his last robbery.

He said that he had read the story "The Case of Summerfield" several years earlier.

When he was searching for a name, that one just popped into his mind. He chuckled at the stir

his verse had created when signed by the name Black Bart.

On June 30, 1864, supposed Confederate troops held up the Placerville stage, and Captain

Henry M. Ingraham, C.S.A. receipted to Wells Fargo for the treasure. Then in 1871,

a San Francisco lawyer, William H. Rhodes, under the pen

name "Caxton"

resurrected the captain as Bartholomew Graham in a dime novel

story called "The Case of Summerfield," which appeared also in the Sacramento Union.

Graham, known as "Black Bart" according to Rhodes, had been "engaged in the late

robbery of Wells Fargo's express at Grizly Bend!"

He was an "unruly and wild villain" who wore all black, had a full black beard and a mess

of wild curly black hair.

It should be noted that Charles Boles never wore black nor did he have a beard nor was his hair black.

Of more importance was the rest of his description:

"He is 5 foot 10.5 inches in height, clear blue eyes and served in the civil war."

Stage drivers never forgot those "clear blue eyes."

By using the name Black Bart, Boles took advantage of an established dime novel bad guy.

So the robber Black Bart was already known as someone to be feared.

If you were robbed by Black Bart, you didn't argue, you just gave up the loot.

Black Bart the P o 8

At the fourth and fifth robbery Bart left a note. He signed the note with a name that would go down in western history: "Black Bart, P o 8." The letters and number mystified lawmen as much as the name Black Bart. Any tracking posse found no trace of the elusive bandit, and superstition had it that the stage indeed had been robbed by a ghost. There were only two poems but it is one of the most recognizable parts of the legend.

At the fourth robbery:

"I've labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches

But on my corns too long you've tread,

You fine-haired sons-of-bitches.

Black Bart, the P o 8"

At the fifth robbery:

"To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat

And everlasting sorrow.

Yet come what will, I'll try it once,

My conditions can't be worse,

But if there's money in that box,

It's munny in my purse.

Black Bart, the P o 8"

Note: A little know fact is that on the first poem there was also a note scribbled under the verse. The poem and the note had each line written in a different hand. It is thought that Bart did this to disguise his handwriting.

The note reads:

Driver, give my respects to our old friend, the other driver. I really

had a notion to hang my old disguise hat on his weather eye.

After Bart's release from prison there was another robbery where a poem was left in the same fashion that Bart always left his poems. Detective Hume examined the note and compared it with the genuine Black Bart bits of poetry of the past. He declared the new verse a hoax and the work of another man, declaring that he was certain Black Bart had permanently retired. This gave rise to the later notion that Wells Fargo had actually pensioned off the robber on his promise that he would stop no more of its stages, paying him a handsome annuity until his death.

This is the third poem that was NOT written by the P o 8

So here I've stood while wind and rain

Have set the trees a'sobbin'

And risked my life for that damned stage

That wasn't worth the robbin'.

Home | Why Bart | Legend Begins | C.E. Boles | Legend Ends | Prison | Robberies | Family Tree | Trivia | Plaque | ????

Want to contact us? E-mail the Webmaster