California's Infamous Stage Robber

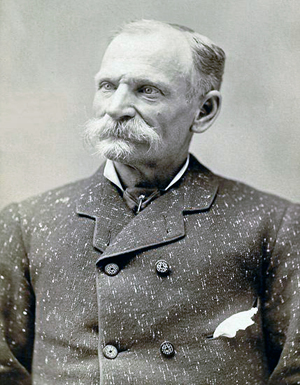

CHARLES E. BOLES

Photo courtesy

Calaveras County Historical Society.

Charles E. Boles Signature

Charley, as everyone called him, had a common school education but excelled at sports and was probably, for his weight, the best collar and elbow wrestler in Jefferson County. As a small child he had smallpox but was strong enough to overcome it. It was an endurance quality that would serve him well during his gold mining days, during the Civil War and again during his career as Black Bart.

In 1849 Charley and cousin David set out for the goldfields, spending a hard winter in either St. Joseph or Independence, Missouri. They arrived in California in early 1850 and started mining at the north fork of the American River, near Sacramento. Gold mining in the early days was back-breaking work, often with few rewards. Charley and his cousin mined for only a year before retuning home in 1852. Charley insisted on returning to the California gold fields. This time his brother, Robert, accompanied Charley and David to California. However, tragedy struck on this trip, and both David and Robert were taken ill and died in California soon after their arrival. Charley continued mining for two more years before returning home. Charley then went to Illinois where he married Mary Elizabeth Johnson in 1854. They had four children.

In 1861 the Civil War broke out and in 1862 Charley volunteered to join the Union Army. He enlisted for three years with the 116th Regiment of the Illinois Infantry on August 13th, 1862 at Decatur. On July 1, 1863 Charley was promoted to a First Sergeant in Company B and twice had the opportunity of becoming a Lieutenant. On May 26, 1864 at Dallas, Georgia, he received a severe wound in the right side/abdominal region. Considering the conditions of the wound, it is remarkable that he survived. After his recovery Charley returned to his unit and fought in the battle of Atlanta. Charley served honorably as a soldier during the war and was mustered out as a First Sergeant on June 7, 1865.

After the war Charley returned home and started farming again, but farming was not to his liking and he became restless. After all the time in the army and living in the open air, along with memories of the goldfields, Charley decided he could make more money mining than farming. With his wife's permission he left his family to look for gold. Charley went to Montana and located a small mine1 that he worked with a miner named Henry Roberts2 from Missouri. Charley's mine made use of long "toms," which are basically troughs of boards 12 feet long and 8 to 10 inches deep. Covering the end of the tom was a metal sheet with holes in it to let grains of sand and gold pass through. A steady stream of water was the key to the operation. One day several men tried to buy Charley out, but he refused believing that he was better off keeping the mine. That decision was significant to Charley. The men who had approached him were connected to Wells Fargo and they wanted the land the mine was on. They cut off Charley's supply of water and he was forced to abandon the mine. Charley was very angry and he wrote about it in letters home. In one letter he said "I am going to take steps," but never said what steps. It seems according to his own letters it was the forced abandonment of his mine that made Charles Boles turn on Wells Fargo and make them his target. The last letter3 Mary Boles received from Charley was from Silver Bow, Montana, dated August 25, 1871. In it he said he had made his stake, could take care of his family, and was about to return home to his wife and children. After that she did not hear from him again until after he had been captured and identified as Black Bart in 1883. Mary thought he had died4.

Now things start to change. Exit Charles E. Boles, Enter Charles Bolton, a dapperly dressedman in his mid-fifties. He stood 5 feet 8 inches tall with clear blue/grey eyes and he sported a brushy moustache. He was a man who liked to live well and intended to do just that. He stayed in fine hotels, ate in the best restaurants and wore the finest clothes. Now all he had to do was find a way to earn a living to support his preferred lifestyle, and he found a dandy.

After robbing 28 Wells Fargo stages over a period of eight years Bart was captured and served four years and two months of a six year sentence in San Quentin Prison. On January 21, 1888, Black Bart walked out of prison a free man. Bart went back to San Francisco and took a room at the Nevada House located at 132 Sixth Street. There Wells Fargo kept close track of him and Bart did not like it. In February, 1888 Bart left the Nevada House and vanished. Wells Fargo tracked him to the Palace Hotel5 in Visalia where a man answering the description of Bart checked in and then disappeared. That was the last time anyone saw Black Bart, February 28, 1888.

In 1892 Mary Boles listed herself in the city directory as the widow of Charles E. Boles. She may have known more than she was telling, but then again she may have just given up and done it to get on with her life.

Supposedly In 1917, a New York newspaper printed an obituary for a Charles E. Boles, a Civil War veteran. If this was Bart, he would have been 88 years old.

1 In a letter home written April,4, 1869, Charles said he had just purchased a mine for $260 in gold dust.

2 The 1870 Montana Census shows Charles Boles and Henry Roberts living on a mining claim near Deer Creek, close to Silver Bow, the present day Butte.

3 During his early times in Montana, Charles wrote to Mary as many as four time a week. Few letters survive today: most letters contained sentiments of love and affection but contained little information about his life or plans.

4 When the letters from Charles suddenly stopped, Mary thought Charles was dead. She heard a rumor that he and a party of travellers had been killed by Indians. It would be twelve years before she found out that Charles was not only alive but was also the bandit, Black Bart.

5 Local Historians in Visalia, CA dispute which hotel Bart stayed in at Visalia. Local historians claim that Bart actually stayed at the Visalia House Hotel. The two hotels were a block apart on Visalia's Main St. The Palace Hotel building still exists. The Visalia House was torn down in 1917.

Black Bart

Photo courtesy Wells Fargo Historical Services

and cannot be reproduced without their permission.

Boles home in Decatur.

Destroyed in the 1980's

Home | Why Bart | Legend Begins | C.E. Boles | Legend Ends | Prison | Robberies | Family Tree | Trivia | Plaque | ????

Want to contact us? E-mail the Webmaster